The very label ‘citizen science’ (as opposed to, say, ‘amateur’ or ‘extramural’) carries the unsubtle suggestion that science should be a participatory democracy, not an unpalatable, autocratic regime. Proponents claim that it has all manner of salutary side-effects. People will get the knowledge they want through direct action, it’s argued, instead of having it shoved down their throats by some Ivy-league elitist. Getting a hands-on appreciation for research will help to dispel the worrisome doubts that certain citizens now possess about the legitimacy of scientific authority. And when it comes to medicine, discoveries of novel therapies are increasingly rare, despite the desperate manoeuvres of the pharmaceuticals industry; citizen participation should speed up research and make it much easier to replicate results. Finally, the retraction and replication crises that have besieged academic journals suggest that ‘proper’ science might not be so proper, anyway. Perhaps it’s time to consider alternatives.

(There are several straw men in that passage. Can you count them?)

and

But things lose their lustre when you look a little closer. It’s not a coincidence that citizen science lowers the cost of research that requires lots of routinised labour. Thankfully, we’re flush with design tools that manage to transform repetitive, mindless behaviour into something strangely fun and addictive: games. Galaxy Zoo, a non-profit, amateur astronomy project initially set up with data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, asks participants to scan millions of celestial images for common galactic morphologies; to keep their attention, players can spell out words with constellations, or win points for certain cute galactic structures. Smartfin, from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, gets surfers to attach a sensor to their boards and collect data on salinity, temperature and the like, all of which is pinged back to Scripps once the surfer makes it back to the beach and hooks up the fin to a smartphone. Hundreds of ‘camera traps’, scattered around the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, capture images of creatures that can then be identified by users at Snapshot Serengeti, thus keeping track of animal populations; to amuse themselves, people can attach comments to their favourite photographs (lolgoats, perhaps, rather than lolcats).

And he goes on from there to find what he considers dubious funding sources and worry at length about who benefits from all this.

Do people who participate in these things consider themselves scientists? Or do they think of themselves as assistants? Collecting data is one thing, figuring out how to use it is another.

NSF-funded experiments such as IceCube are required to make their data public, but to get something meaningful out of it requires some disciplines that most people don't pick up on automatically. We're very good at pattern recognition, but sometimes the first pattern you see doesn't actually tell you what you want to know.

A for-instance: you can use the IceCube data to discover that there are seasonal changes in the number of cosmic rays you see. The effect is easy to spot, and someone naively looking at plots might think they'd discovered something new and mysterious. What happens is that at ground level you see the remnants of cosmic ray showers that begin in the upper atmosphere. When the air is warmer (summer), it expands higher, and the cosmic ray showers start higher up. (We keep track of best estimates of upper atmosphere air temperature to go along with our data.)

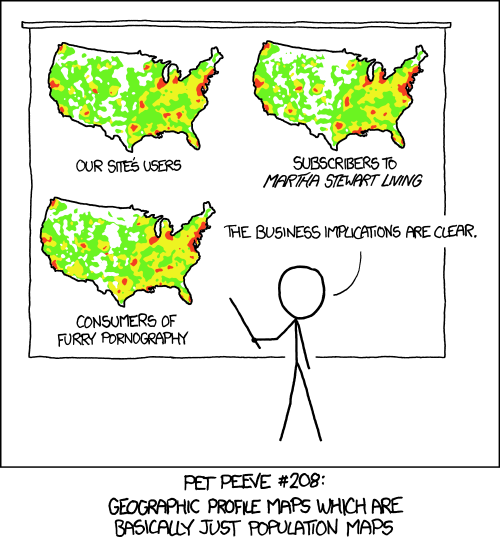

Or you could use something like those population density maps in the cartoon above to discover that there are more crimes where there are more people. Not a surprise: if you look instead at the number of crimes divided by the number of people (the rate), you'd find that the distribution doesn't look the same--some places with more people have higher crime rates, others not so much. You could see how the violent crime rate varies with the rate of car ownership, or density of bars, or rate of single parent households. It isn't hard to think of things to compare it with, and with a little training you can figure out how to study the problem in one variable. I was going to say "It isn't rocket science," but maybe that's misleading. Keeping track of multiple variable is harder, and figuring out which are correlated with which takes quite a bit of care. (Quiz--if you use the number of schools in an area as one variable, should you also use the number of children as a variable at the same time?)

The basic disciplines that science requires are things I think most people can acquire at some level: how to think about analyzing a problem into its "moving parts," to be strictly honest and willing to challenge your own hypotheses, and so on. Those are good disciplines to have. But studying complex problems is hard enough that most people don't care to invest the time--and some can't manage the math that usually turns up. But so long as I don't delude myself into thinking I'm Rembrandt, I think doing a little drawing myself is good. It can help you see. Likewise, learning to do a little scientific analysis can help you see.

Justin Vandenbroucke developed a cool cosmic ray detector that anyone can carry with them. If enough people use it, the distributed data collected might be useful in discovering patterns in cosmic ray fluxes in the Earth's magnetic field (for example). Right now it is mostly just educational. And most of the people running the app are concentrated in a few places in the US and Europe, so the detectors don't have a lot of planetary coverage.

Spencer Axani designed a little box muon detector that lights up when a charged particle goes through. He had a stack of these in the lab across from my office, and you could sometimes see where several lit up in a line. One of these boxes is a toy. A stack of them is a demonstration system. If there were a way to collect data from them remotely, a hundred thousand spread around would be a cosmic shower detector.

Having a cosmic ray detection app, or a box, doesn't teach me much about science, or how it works. That's a shame. But it helps teach about what's around us that we don't notice--just like the people counting moth populations.

No comments:

Post a Comment